The selected artists

Summer 2025

This new collection of artwork speaks to diverse yet common experiences of caregiving from around the world. Themes of alienation, solidarity, mundanity, ambivalence, exhaustion, resistance and repair appear almost universally in contemporary expressions of motherhood. Do these works gesture towards a common understanding of the devaluing of gendered labour?

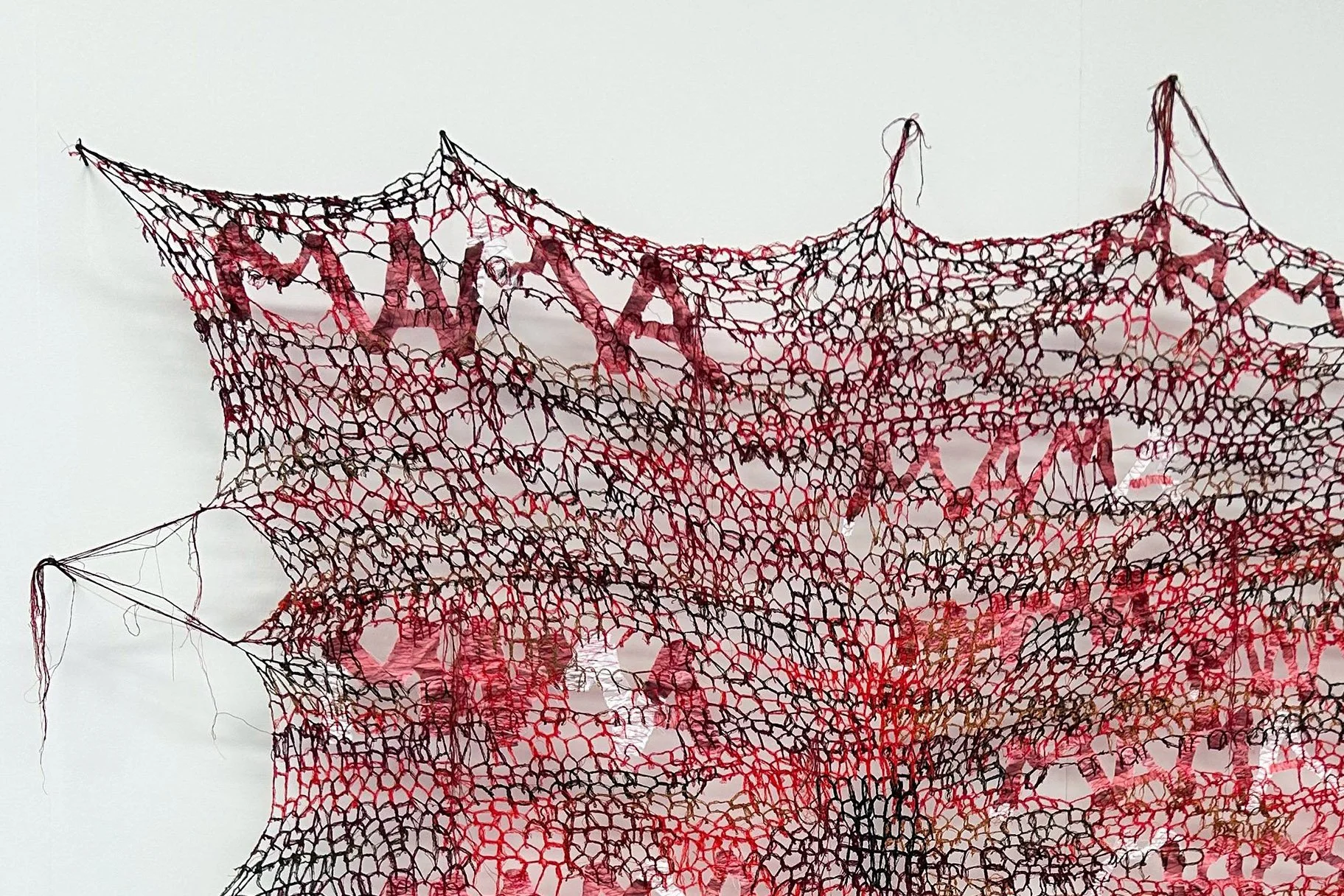

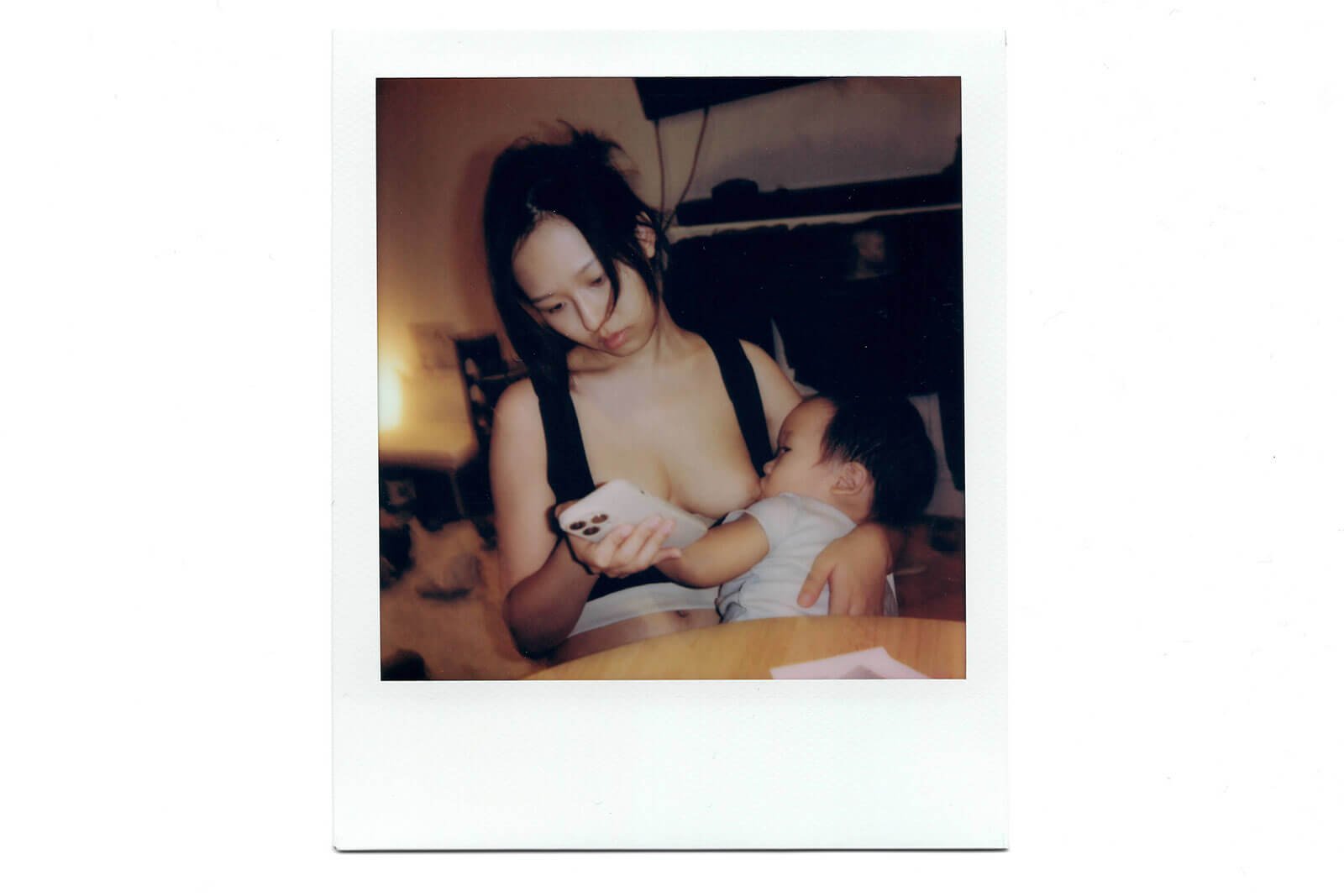

“I am not here! Am !?” a potent universal question posed by Iara Sales in her photo series of the same name. Sales breaks through the fourth wall with a direct gaze that asks for recognition, dialogue and co-participation. There is exhaustion from the mileage mothers maintain which is too often kept hidden. The weight of that reality is expressed in Helen Barff’s work ‘Stack’. The work is much heavier than it appears. Some mothers are resigned to a fate that is exacerbated under the tenets of capitalism. Many work in seclusion; others must work in silence, but the expression of a certain ambivalence to the work is not shocking. Madam Pagu aptly tackles the mother-child bond in “A FORCA”. These are ties that bind us. We are linked no matter the circumstance.

The Essential Work exhibition is a curation of distinct perspectives of artists/mothers. There is a serenity in looking from a distance, seeing from a new vantage point, noticing the self out of the boundaries of societal expectations and systems of profit. There is a need for a fresh start. “Brekkie” by Kate Hynes conjures a moment of pause and sits in this reflection. Behind the closed door, how long can one keep the outside world at bay? Without the effort and the acts of grace and continued love, the system itself would collapse.

How does art function in a world in need of change?

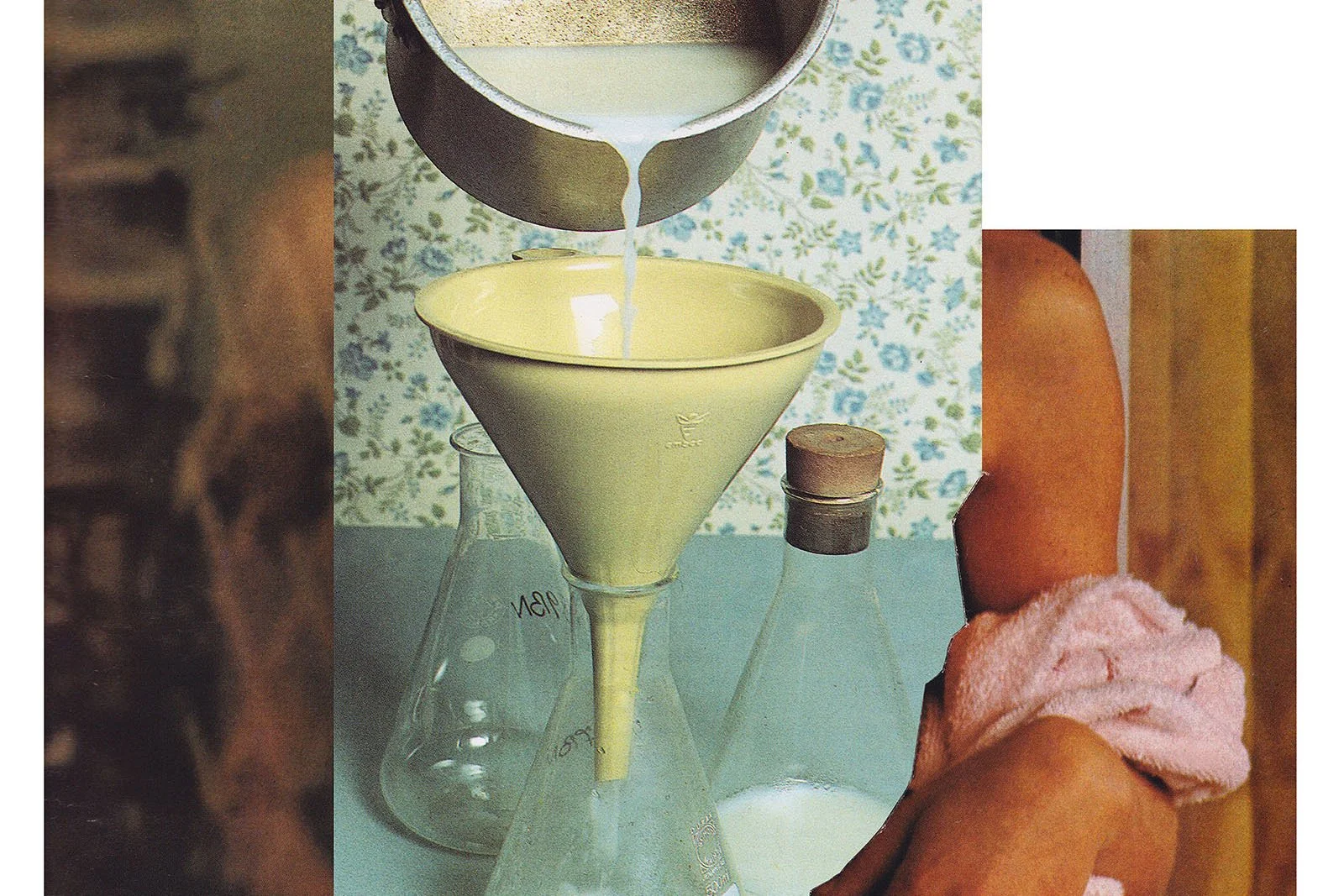

The art itself may not change the system.The power sits within people's continued expression in community, shared experience and rallying in great numbers to demonstrate the true value of this motherhood. The context in which we all labour as workers, artists, mothers and carers is that of a socioeconomic system characterised by the commodification and industrialisation of more and more parts of our daily lives. Michal Nahman and Susan Newman’s research in India on the commercialisation of human milk sought to understand how the labour of milk providers is devalued while the technoscientific ‘processing’ and commercial selling of that milk becomes imbued with market value that leads to profits for corporations. Sanne Steijger’s “Ordinary Milk” zooms into the materiality of milk as medium revealing how much is obscured within, paralleling the hidden nature of labour exploitation. Meanwhile, milk production and processing is a hybrid of labour, embodied and science/technology practices. “Milk Maid” by Kate Street juxtaposes a body and bottling of milk, part domestic and part scientific.

How do we get off this conveyor belt?

Feminist activists and scholars have for decades reiterated the injustices that emerge from a capitalist system where social reproductive labour is devalued and systematically excluded from how economic value is accounted for. Feminist activists and artists since the 1960s have variously emphasised the potential for resistance and emancipation in rendering visible what has been systematically made invisible by prevailing social structures.

Several artworks in this collection demonstrate this tradition. Alana Ortiz’s long exposure photograph of laundry work shows the labourer blurred by her activity, almost to the point of invisibility. What would putting a market value on this work entail when social care workers in capitalist enterprises are paid so little? In “Mothers & Machines”, Jessie Edwards-Thomas begs us to ask the question: What if reproductive work was fully organised as a capitalist enterprise? Can emancipation ever be achieved by extending capitalist logic? Our answer is no.

Corporate profiteering relies on unpaid social reproductive labour conducted in hidden domestic abodes. Society has been structured as if consisting of separate spheres: one in which the conditions of life and living are reproduced, concealed away in private domestic realms, and another productive sphere where economic value is created that is highly visible and legitimised in society. In this way, social reproductive work appears as free gifts of nature to capitalists. The simultaneous invisibility and essential nature of socially reproductive work appears as a paradox when in fact they follow a coherent logic within the capitalist system. Boaventura’s work is a starting point. “Techtonics” portrays the chasm between these spheres and speaks to the need to stitch them together.

The logic of the capitalist system becomes contradictory when the profit imperative undermines the very conditions for social reproduction. Low wages and rising costs of living continue to be experienced globally along with absent or inadequate health and welfare systems are vivid examples. The destruction of ecosystems necessary for life, land destruction by imperialist wars, paid for with our tax dollars, exist with no benefit to citizens. Everyone can see that the system is broken as visualised in ‘Glass House’ by Kate Cameron.

In an interview with the British magazine Woman’s Own in 1987, Margaret Thatcher declared that “[T]here is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families.” In this statement, she summed up her vision of the world that had been on track throughout her leadership and the US leadership of Ronald Reagan. Neoliberalism shifted the focus from collective action and social responsibility towards individual autonomy and free markets. There has been no realignment.

One manifestation of neoliberalism is the toxic corporate individualistic ideology of work-life balance when, in fact, many caregivers face the impossible reality of work-work. This is represented in Rania Atef’s film in which a woman repeatedly attempts to keep household objects from falling off balance. In 46 seconds, Jen Mcgowan’s stop motion film “I don’t know how you find the time” speaks to admonishment, admiration and disbelief of her own juggle between art school, teaching and parenting.

Why is solidarity important?

These are all societal problems that require collective responses. Creative social protest, such as long standing Mothers’ Strike action, demonstrates the necessity of collective continuous resistance. As essential workers, can mothers ever really go on strike?

The overload and strain that occurs in private can lead to more isolation. The destruction is evident. The work of Clarice Goncalves, ‘Universally Deplored and Respected’, asks, “Who cares for those who care?” More voices are needed for collective transformation and solidarity. Envisioning a world where solidarity and care exist beyond blood kinship, as some of the artists do, echoes Donna Haraway* who stated: “I am sick to death of bonding through kinship and “the family,” and I long for models of solidarity and human unity and difference rooted in friendship, work, partially shared purposes, intractable collective pain, inescapable mortality, and persistent hope … Ties through blood … have been bloody enough already.”

Envisioning ways out of the radically atomising nature of the prevailing system is a necessity, not a choice. We must collectively understand the origins and mechanisms of oppression so that we can effectively resist them.

Is what mothers/artists around the world are resisting today the same as 20, 30 or 40 years ago? And, how does it vary across contexts and continents? Is this the work of a new type of mother artist more informed by current material struggles, contemplating how to resist today? There is an intensification in the concentration of economic power that is harder to ignore. We face new infrastructure ‘assisted’ by technology that demands state surveillance and control. How do we overcome the individualising cultures that prevail and distract? Care work is in desperate need of re-visioning for the future. These artists enrich the visual landscapes that inspire the conversations that will help us to act.

We thank the artists for their work. Please explore the This is Essential Work new artist cohort. Engage with their work for the call, their personal websites and perspectives. All artists can be contacted directly for sales and other inquiries.

*Quoted from Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium. FemaleMan_Meets_OncoMouse: Feminism and technoscience.

About This is Essential Work

If women indeed hold up the world, why are those who perform essential social reproductive labour not paid, or paid so little? Why is our “essential” work devalued? We cannot be content with simply making visible that which is hidden. Nor can we just focus on whether we are paid or not paid for reproductive work. We need to offer a broader view of how, where, when and why our labour and body parts are exploited in the creation of economic value.

In the first edition of This Is Essential Work, we sought to shine a light on the actual labour of social reproduction. The exhibition focussed on the care and nurture of childbearing and childcare in particular. The work highlighted the invisibility of this labour, which tends to be obscured by maternalistic notions of love and sacrifice. Some of the artworks engaged with questions of commodification, while others evoked the endpoints of work, i.e. exhausted bodies, a tidy sink, a satisfied child. The balance, juggle and contradictions between paid-work and unpaid labour was evident.

Since our first call for artists, the exploitative realities of reproductive care labour have become popular to talk about. The incongruences have also become more popular as the subject of artistic endeavour. The notion, however, that we can dismantle the very systems of social reproductive exploitation is still not that popular.

For the second edition, we invited artists to engage once again in the development of ideas around the valuation and devaluation of reproductive labour. We invited artists to share how their practice and artwork attempts to visualize the ways in which capitalism systematically devalues social reproduction and care. It’s a common problem within a system of profit. Bigger profit means more grandiose (but often invisible) exploitation. As those in positions of power continue to hold us captive within systems of economic manipulation and harm, how can we change society to avoid valuation based on gender, race or class? Art and artists play a major part in envisioning a different future.

This Is Essential Work remains an online open-access intersectional feminist exhibition. It was initiated by academic mothers and creators, Michal Nahman (UWE, Bristol) and Susan Newman (Open University), who seek to explore a visual dialogue between artists worldwide and their academic research (as anthropologist and economist). The initial research began in Bengaluru, India, just before the Covid 19 pandemic. Mothers’ provisions of their own breastmilk were being sold to a private company that was processing and selling it at a profit. This had never been done in such a way before. In 2022, the This Is Essential Work team was formed with artist Yuko Edwards to develop the exhibition.

This year, exactly five years on, Nahman and Newman returned to India with the guidance of Bengaluru-based academic mother - Ranjini Ragavendra. The team’s focus was to better understand processes of extraction and exploitation in regards to the complex experiences of women as they directly and indirectly support the creation of economic value. They met with milk providers, social workers and milk banks. In seeking to highlight the perspectives of those centrally involved, and have that shape the theory, the research team went to rural regions of Karnataka to listen and document the voices of women and the many different views on whether commercial interests should enter the realm of human milk provision. Many of those who were surveyed pointed towards the unethical and exploitative practices of buying and selling mothers milk/breastmilk. For those women who have very limited access to paid work, a meagre income, however limited, is not easily disregarded as few opportunities for paid work exist. We see parallels in industries of surrogacy, egg and sperm providing, blood, uterine, and organ donation.

Through this project, we want to build a network of artists, scholars and activists to explore together and to act together with the aim of changing the system that oppresses us all.

The Jury

Michal Nahman

Born: Montreal, Canada

Lives: Bristol, England

Michal researches reproductive politics and food justice, using ethnographic methods and multimodal expressions such as film, photos and theatre.

URL: Michal Nahman

Susan Newman

Born: Hong Kong

Lives: Bristol, England

Susan Newman is a political economist and former human milk producer interested in processes of commodification and why things are priced in the way that they are.

URL: Susan Newman

Yuko Edwards

Born: Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Lives: Bristol, England

Yuko Edwards is an artist/mother interested in concepts of self and social identity. Her work uses history as a starting point to retell stories and interrogate existing social structures.

IG: @yukoedwards

This is Essential Work 2022 Exhibition

From our mother/artist open call, we received over 700 pieces of art from around the world. The volume of work was both moving and invigorating. The artists you see on the following pages bring global perspectives from ethnically and geographically diverse backgrounds. We have early-stage artists to mid-career makers.

Is it possible to create networks of mother artists and activists to support and encourage one another to continue the necessary work of forging change? From what we have learned from this process, a resounding “Yes, we believe so.”

In our inaugural This is Essential Work exhibition, our artists come from Brazil, Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom, (London via) China, (New York via) New Delhi, Nigeria, and more. We have had the privilege to see unique art questioning familiar social constructs and barriers, topics that are common discourse in our academic circles. Our selection of the work was guided in the first instance by how individual pieces spoke to the issue of how social reproductive work is valued in society and to the lived experience of performing this labour. It was important to us to select work that drew out different historical experiences across class, cultures, and geographical space and time. We wanted the work to be intersectional, and we wanted to showcase work by artists at different career stages. The artists’ own words in describing their experiences and practice were also taken into account in our selection.

We were excited to see artwork grounded in the physical aspects of maternal labour, in and through bodies. The art shows multiple forms of social reproductive work: conceiving, feeding, clothing, cleaning, teaching, and entertaining. We see how the act of play is an effective tool in the ways that mothers impart knowledge to children. Too often this maternal labour is overlooked by society at large. The fatigue and the sacrifices of the work of social reproduction moulds the next generation. Many of the works show us the embodied nature of mothering, the physicality of this labour, and its transformative effects on the bodies of workers is manifest and inescapable. All this at a time when some states are removing women’s autonomy over their reproductive bodies through legislation. This artwork is a political act.

Please explore our exhibiting artist’s work, their websites and social media. They can be contacted directly for additional inquires and purchases.

Summer 2022

How much is the work of social reproduction valued in our world? Nurturing, feeding, bearing, and caring work is crucial to the survival of humans everywhere, yet the world rarely perceives it as work.

This Is Essential Work is an online open-access intersectional feminist exhibition initiated by academic mothers and creators, Michal Nahman (UWE, Bristol) and Susan Newman (Open University) in response to their experiences and interdisciplinary research on the commodification of breastmilk and forms of exploitation of women’s bodies and labour.

This exhibition emerged from research funded by a UWE Vice Chancellor’s Award for Interdisciplinary Collaborative Research conducted just before the Covid-19 pandemic, in Bengaluru, India, into mother’s provision of “excess” breastmilk to a private company that was processing it and selling it at a profit. Why did mothers give their milk? Because they were convinced that they were helping others in need and that they could do this without cost.

This is not unique to breastmilk. It is not enough to just write about this in the distant realm of academia. Those who engage in social reproductive labour work hard; giving in the home, caring for their own children, for other peoples’ children, and for other family members in a multitude of ways. The way that social reproduction is organised in capitalist society has relied upon and entrenched social divisions and continued oppression along classed, gendered and racialised lines. Those from oppressed groups are on average paid less, more likely to be in precarious employment, and in jobs that are undervalued in a capitalist society, such as care work.

For this exhibition, the art conveys how work and bodies get devalued. This feminist exhibition is about showcasing this gendered work: to acknowledge, to grieve, and importantly, to connect with one another.

We are showcasing mother/artists who question the value that society puts on their work, including all kinds of labour. The list of our Essential Work is endless and it holds up the world.

We ask:

What is the value of reproductive labour today? How does it relate to other forms of paid and unpaid work?